Unfinished

Ruins and decay of contemporary

An interesting example is the group of architects SITE, who in these years designed most of the BEST warehouses in America, already envisioning them in a state of ruin. In Italy, during these same years, we find Cesare Brandi, who with his “Theory of Restoration” begins to analyze the aesthetic dimension of ruins. Although the ruin may have lost its original “beauty,” Brandi argues that it can acquire a new kind of beauty, dictated by other factors such as the intervention of nature or the passage of time.

In this overview, it is also fitting to mention the text “Architecture and Disjunction” written by Bernard Tschumi in 1996, where he presents a particular depiction of Villa Savoye, just days before its restoration. Through this depiction, Tschumi aims to define the true moment of architecture as the moment of decay, where the building is suspended between life and death, and the experience of space becomes the concept itself.

Around the same time, the artist Anselm Kiefer created the 2004 installation “The Seven Heavenly Palaces” in the Bicocca hangar in Milan, constructing seven concrete towers, in ruins, clearly precarious and decaying, seemingly caught in the moment just before they fall. These structures also take on symbolic meanings, almost as if revealing a path to the afterlife. It is thus evident that during these years, there is a pursuit of an aesthetic of ruin, rooted in the search for the “sublime” and in the desire to evoke anguish, shock, and emotion. This shows how, even after millennia, ruins continue to seduce and stimulate the human soul, laden with new meanings and values.

Finally, one of the most interesting theories concerning ruins today is that of the French anthropologist Marc Augé. According to him, ruins speak of a multiplicity of pasts that refer to nothing; they are not the time of history or dates but a “pure” time. Today, there is a need for this kind of time, as it is the only way to gain awareness of duration and to understand history itself. Thus, if the past has produced ruins capable of evoking memories and preserving the essence of time, the contemporary world has produced only rubble—remnants unable to tell or communicate anything, as they lack history. While ruins imply the ability to remember, rubble reflects the desire to erase the past, telling no story. So today, what we call ruins belong to a distant past and are loaded with history that can be told to those who study them, while so-called unfinished works could be defined as the rubble of a contemporary world too fast to produce true ruins.

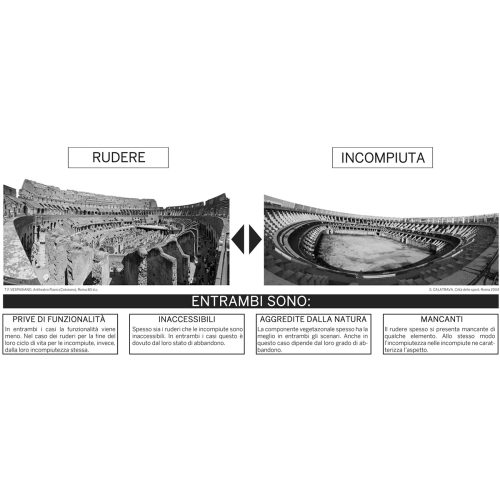

The parallel between a ruin and an unfinished work is not only spatial and formal. There are many shared elements: nature’s invasion is a constant in both cases; the lack of parts, which in the case of ruins is due to material loss, while in unfinished works, it is due to incomplete construction; the inaccessibility of these spaces; and finally, the state of abandonment that projects both ruins and unfinished works into the contemporary interest in architectural waste, no longer seen as exceptional but now recognizable in specific landscapes awaiting redevelopment. As Rem Koolhaas defines it in “Junkspaces,” what modernity has produced is not modern architecture, but junkspaces—what remains after modernity has run its course, or rather, what coagulates while modernity is still in progress.

Returning to the relationship between ruins and unfinished works, it is interesting to analyze the concept of ruin as defined by Franco Purini in “Composing Architecture.” According to Purini, between the beginning of construction and its completion, the building will take on an appearance that anticipates its fate (as a building in ruin). Thus, the unfinished work can be perceived as a prefiguration of the hypothetical transformation into a ruin that the work will undergo at the end of its life cycle. Furthermore, Purini explains that the ruin is the only means through which one can truly contemplate the pure essence of a building’s architecture, as it is devoid of functionality and stability. Thus, there are two moments in which a building reveals its pure essence: when the building is in its construction phase, i.e., incomplete, and when the building is in a total state of abandonment.

Unfinished works can be defined as true *CONTEMPORARY RUINS*, meaning those works that are reduced to the state of ruin even before they have a chance to become architecture.

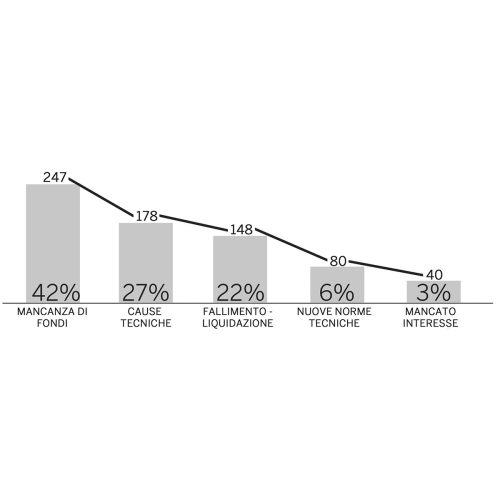

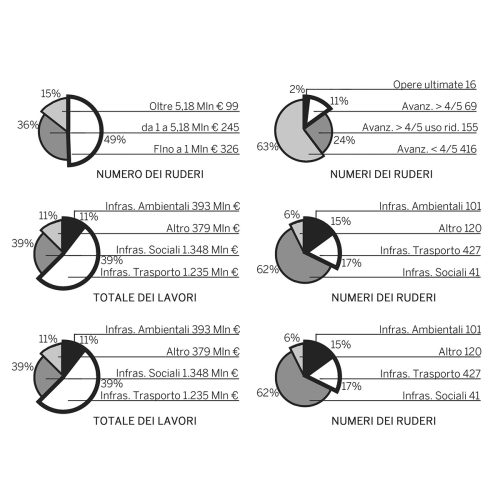

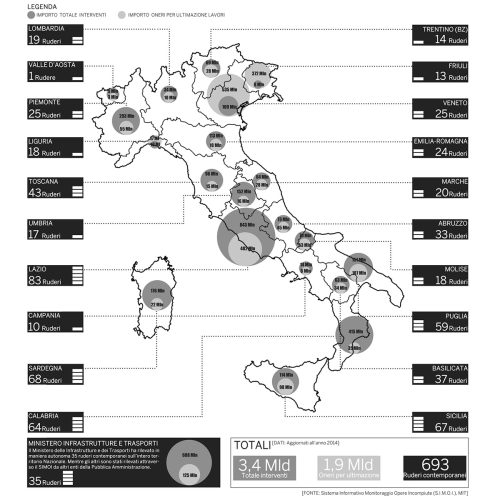

These contemporary ruins, cataloged in Italy by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport through the SIMOI (Information System for Monitoring Unfinished Works) in 2013 and published the following year, number 693—a number that unfortunately will continue to grow year after year. The phenomenon of unfinished works is spread quite evenly across all Italian regions. The main peaks can be seen in Lazio (82 unfinished works), Sardinia (68), and Sicily (67). The region with the fewest contemporary ruins is Valle d’Aosta, with only one unfinished work worth 5 million euros. The total investment for these works amounts to around 3.4 billion euros, while the figure for completing the entire unfinished heritage is 1.9 billion.

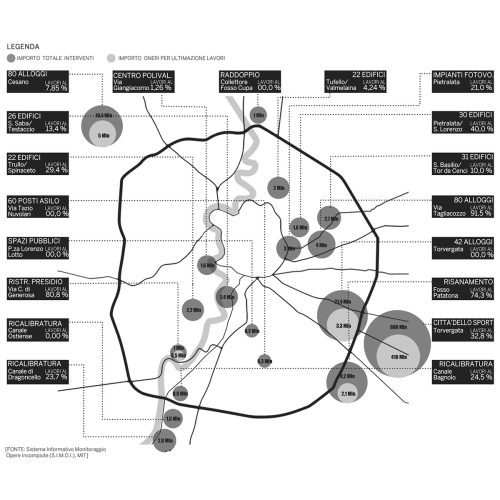

SIMOI awarded the Lazio region the title for the most Unfinished Works, cataloging 83 contemporary ruins for a total of 665 million euros in work and 421 million for their completion. The province of Rome, with 36 unfinished works, is the regional leader.

Following are Frosinone with 23 ruins, Viterbo with 13, Latina with 8, and finally, Rieti with only 3 unfinished works. The province of Rome is also the one with the most municipalities (9) featuring unfinished works, with Rome itself leading with 19 contemporary ruins.

Rome, definable as the capital of the unfinished, holds the record for public money spent on unfinished works. SIMOI’s estimate stands at around 665 million euros in total funding and 421 million for the completion of the works. The majority of Rome’s unfinished works consist of public housing buildings scattered evenly across the entire municipal area.

The most expensive construction project, not only in the municipality of Rome but across the entire national territory, is the *City of Sport* by Santiago Calatrava, exceeding 600 million euros, with an estimated 410 million euros required for completion.

The project by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport (MIT), presented at the conference “UNFINISHED WORKS: WHAT FUTURE?” (Rome, January 13, 2015), outlines five distinct points, which will be implemented through an urgent legislative proposal, also in view of the new procurement code.

An interesting example is the group of architects SITE, who in these years designed most of the BEST warehouses in America, already envisioning them in a state of ruin. In Italy, during these same years, we find Cesare Brandi, who with his “Theory of Restoration” begins to analyze the aesthetic dimension of ruins. Although the ruin may have lost its original “beauty,” Brandi argues that it can acquire a new kind of beauty, dictated by other factors such as the intervention of nature or the passage of time.

In this overview, it is also fitting to mention the text “Architecture and Disjunction” written by Bernard Tschumi in 1996, where he presents a particular depiction of Villa Savoye, just days before its restoration. Through this depiction, Tschumi aims to define the true moment of architecture as the moment of decay, where the building is suspended between life and death, and the experience of space becomes the concept itself.

Around the same time, the artist Anselm Kiefer created the 2004 installation “The Seven Heavenly Palaces” in the Bicocca hangar in Milan, constructing seven concrete towers, in ruins, clearly precarious and decaying, seemingly caught in the moment just before they fall. These structures also take on symbolic meanings, almost as if revealing a path to the afterlife. It is thus evident that during these years, there is a pursuit of an aesthetic of ruin, rooted in the search for the “sublime” and in the desire to evoke anguish, shock, and emotion. This shows how, even after millennia, ruins continue to seduce and stimulate the human soul, laden with new meanings and values.

Finally, one of the most interesting theories concerning ruins today is that of the French anthropologist Marc Augé. According to him, ruins speak of a multiplicity of pasts that refer to nothing; they are not the time of history or dates but a “pure” time. Today, there is a need for this kind of time, as it is the only way to gain awareness of duration and to understand history itself. Thus, if the past has produced ruins capable of evoking memories and preserving the essence of time, the contemporary world has produced only rubble—remnants unable to tell or communicate anything, as they lack history. While ruins imply the ability to remember, rubble reflects the desire to erase the past, telling no story. So today, what we call ruins belong to a distant past and are loaded with history that can be told to those who study them, while so-called unfinished works could be defined as the rubble of a contemporary world too fast to produce true ruins.

The parallel between a ruin and an unfinished work is not only spatial and formal. There are many shared elements: nature’s invasion is a constant in both cases; the lack of parts, which in the case of ruins is due to material loss, while in unfinished works, it is due to incomplete construction; the inaccessibility of these spaces; and finally, the state of abandonment that projects both ruins and unfinished works into the contemporary interest in architectural waste, no longer seen as exceptional but now recognizable in specific landscapes awaiting redevelopment. As Rem Koolhaas defines it in “Junkspaces,” what modernity has produced is not modern architecture, but junkspaces—what remains after modernity has run its course, or rather, what coagulates while modernity is still in progress.

Returning to the relationship between ruins and unfinished works, it is interesting to analyze the concept of ruin as defined by Franco Purini in “Composing Architecture.” According to Purini, between the beginning of construction and its completion, the building will take on an appearance that anticipates its fate (as a building in ruin). Thus, the unfinished work can be perceived as a prefiguration of the hypothetical transformation into a ruin that the work will undergo at the end of its life cycle. Furthermore, Purini explains that the ruin is the only means through which one can truly contemplate the pure essence of a building’s architecture, as it is devoid of functionality and stability. Thus, there are two moments in which a building reveals its pure essence: when the building is in its construction phase, i.e., incomplete, and when the building is in a total state of abandonment.

Unfinished works can be defined as true *CONTEMPORARY RUINS*, meaning those works that are reduced to the state of ruin even before they have a chance to become architecture.

These contemporary ruins, cataloged in Italy by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport through the SIMOI (Information System for Monitoring Unfinished Works) in 2013 and published the following year, number 693—a number that unfortunately will continue to grow year after year. The phenomenon of unfinished works is spread quite evenly across all Italian regions. The main peaks can be seen in Lazio (82 unfinished works), Sardinia (68), and Sicily (67). The region with the fewest contemporary ruins is Valle d’Aosta, with only one unfinished work worth 5 million euros. The total investment for these works amounts to around 3.4 billion euros, while the figure for completing the entire unfinished heritage is 1.9 billion.

SIMOI awarded the Lazio region the title for the most Unfinished Works, cataloging 83 contemporary ruins for a total of 665 million euros in work and 421 million for their completion. The province of Rome, with 36 unfinished works, is the regional leader.

Following are Frosinone with 23 ruins, Viterbo with 13, Latina with 8, and finally, Rieti with only 3 unfinished works. The province of Rome is also the one with the most municipalities (9) featuring unfinished works, with Rome itself leading with 19 contemporary ruins.

Rome, definable as the capital of the unfinished, holds the record for public money spent on unfinished works. SIMOI’s estimate stands at around 665 million euros in total funding and 421 million for the completion of the works. The majority of Rome’s unfinished works consist of public housing buildings scattered evenly across the entire municipal area.

The most expensive construction project, not only in the municipality of Rome but across the entire national territory, is the *City of Sport* by Santiago Calatrava, exceeding 600 million euros, with an estimated 410 million euros required for completion.

The project by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport (MIT), presented at the conference “UNFINISHED WORKS: WHAT FUTURE?” (Rome, January 13, 2015), outlines five distinct points, which will be implemented through an urgent legislative proposal, also in view of the new procurement code.

The contemporary ruin examined for the thesis research is the City of Sport in Tor Vergata, which, as previously mentioned, is the most expensive construction project in the entire national territory. The ambitious project by the Spanish starchitect Santiago Calatrava envisioned the creation of a university sports complex with two main buildings: a sports hall made up of two spectacular reinforced concrete and steel structures called “sails,” and a spiral tower about 90 meters high intended for the rectorate of Tor Vergata University. The whole was to be surrounded by student housing and other university services immersed in a large urban park characterized by a shape inspired by the Circus Maximus. A monumental complex to be presented as the crowning glory of the Eternal City for the 2009 World Swimming Championships.

To date, only the steel skeleton of one of the sails of the City of Sport remains at the construction site—an imposing ruin abandoned on the Roman outskirts. An unfinished work reduced to the state of ruin before it even managed to transform into architecture. A testimony to the programmatic, urban, and political failure of a city still unable to face its ambitions.

The original project, directly assigned to the Spanish architect in 2004 in anticipation of the 2009 World Swimming Championships, was estimated at around 120 million euros. It included three indoor pools and an 8,000-seat arena. The following year, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) informed the City of Rome that for a potential Olympic bid, the construction of a facility with a capacity exceeding 15,000 seats would be necessary. This led to a modification of the original project and a doubling of costs. The construction site, managed by Viannini Lavori S.P.A., began in March 2007, but despite the double shifts of 300 workers, by the summer of 2008, it was clear to everyone that it would be impossible to complete the work in time for the World Swimming Championships, which were eventually held at the Foro Italico, and the construction site was halted. But why was such a structure needed if the Foro Italico was perfectly usable?

After the swimming championships, work resumed intermittently. Despite costs ballooning to 600 million euros, the construction site continued in the hope of a new Olympic bid for 2020. The site was closed again when Prime Minister Mario Monti decided to withdraw the 2020 Olympic bid to avoid exacerbating the country’s already precarious financial situation. In 2012, Mayor Gianni Alemanno found new financiers to secure the 410 million euros needed to complete the project. However, negotiations with the Nec Group International and HRS LTD fell through. Today, the municipality and the University of Tor Vergata have proposed a repurposing of Calatrava’s structures with a project by the same architect, costing an additional 200 million euros. This repurposing would involve converting the structure housing the pools into the Faculty of Biology, as well as creating one of the largest greenhouses in the world, while the sports hall would retain its original function.

An ambitious project, stalled like many others, due to organizational incapacity in managing a work of such magnitude. A symbolic episode not only of a city but of an entire country struggling to evolve.

Marco Tanzilli

Bibliografia

C. BRANDI, Teoria del restauro, Einaudi, Torino 1963.

J.G. BALLARD, La civiltà del vento, Mondadori, Milano 1977.

G. SIMMEL, Die Ruine, Klinkhardt, Leipzig 1911, traduzione di G. Carchia in Rivista di Estetica, 8, 1981.

J. RUSKIN, Le sette lampade dell’architettura, Jaca Book, Milano 1982.

M. AUGÈ, Nonluoghi. Introduzione a una antropologia della surmodernità, Elèuthera, Milano 1993.

B. TSCHUMI, Architecture and Disjunction, The MIT Press, Cambridge 1994.

F.PURINI, Comporre l’architettura, Universale laterza, Bari 2000.

M. DORING, “La nascita della rovina artificiale nel Rinascimento Italiano ovvero il Tempio in rovina di Bramante a Genazzano”, in Donato Bramante: Ricerche, proposte, riletture, a cura di F. P. Di Teodoro, Urbino 2001.

M. AUGÈ, Rovine e macerie. Il senso del tempo, Bollati Borringhieri, Parigi 2004.

R. KOOLHAAS, Junkspace, Quodlibet, Macerata 2005.

G. CLÉMENT, Manifesto del Terzo paesaggio, Quodlibet, Macerata 2005.

S. ZALMAN, The Nun-u-ment. Gordon Matta Clark and the contingency of space, New York 2005.

F. Cellini, “Il rudere”, in Il rudere tra conservazione e reintegrazione. Atti del convegno internazionale (Sassari, 26-27 set 2003), a cura di B. Billeci, S. Gizzi, Gangemi editore, Roma 2006.

A. BRUNO, “I ruderi di nuova generazione”in Il rudere tra conservazione e reintegrazione. Atti del convegno internazionale (Sassari, 26-27 set 2003), a cura di B. Billeci, S. Gizzi, D. Scudino, Gangemi editore, Roma 2006.

J.G. BALLARD, L’isola di cemento, Feltrinelli, Roma 2007.

F. PURINI, Attualità di Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Libria, Melfi 2008.

T. MATTEINI, Paesaggi del tempo. Documenti archeologici e rovine artificiali nel disegno di giardini e paesaggi, Allinea, Roma 2009.

G.MENZIETTI, Rovine contemporanee. Resti dell’architettura Italiana tra gli anni ‘60 e gli anni ’80, Dottorato di Ricerca Internazionale Villard d’Honnecourt, Madrid 2009.

A. UGOLINI, Ricomporre la rovina, Alinea editrice, Perugia 2010.

S.MARINI, Nuove terre. Architettura e paesaggi dello scarto, Quodlibet studio, Macerata 2010.

F. BATTISTI, Valutazioni comparative per lo sviluppo dei processi di riqualificazione del territorio a partenariato pubblico-privato: una proposta di metodo, Dottorato di Ricerca in Riqualificazione e Recupero Insediativo, Roma 2012.